Designing Liberation Technologies

Mobile phones are one of the most rapidly adopted new technologies in history, with usage in all parts of the world rising quickly—and soaring in developing nations. In 2000, there were 16 million mobile subscriptions in Africa; in 2008, there were 376 million. No longer limited to one-to-one communication, mobile phones are mini-computers that provide access to the Internet and a wide array of services from banking to shopping.

Kenya is one of the world’s poorest nations—number 147 of 182 countries in the U.N.’s ranking of human development. The average life expectancy is about 57 years and health care services are not only costly but severely overstretched. Located in Kenya’s capital Nairobi, Kibera is the second largest slum in Africa—home to hundreds of thousands of people crammed into a space the size of Manhattan’s Central Park. There are limited municipal services, and most residents have to purchase necessities such as potable water.

A new course called Designing Liberation Technologies identifies mobile phones as a technology with untapped potential for solving some of the challenges facing the world’s poor. The title seems audacious for a university course—sounding at first too grand in scope and breadth, inviting skepticism from those unfamiliar with mind-bending exercises designed to open the imagination enough to see possibilities. But offer it on a campus such as Stanford, and suddenly the title makes sense. Co-taught by Professor of Political Science, Philosophy and Law Joshua Cohen, the Marta Sutton Weeks Professor of Ethics in Society, and Professor of Computer Science Terry Winograd, the course brings together (mostly) graduate students from across Stanford—students with expertise in business, computer science, design, engineering, and law. Working through Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (the “d.school”), participants in the class collaborate with faculty and students from the University of Nairobi’s computer science department, teaming up to look for ways to marry health care challenges for residents of Kibera with mobile phone applications. The project is a crash course in anthropology, global development, startup venture funding, teamwork, technology application design, and third-world culture, all infused with the d.school’s philosophy of user-centered design. The first run of the class was offered last spring; the course will be offered again in spring 2011.

The time constraint of a one-quarter course was the initial challenge for Cohen and Winograd, who visited Nairobi in February 2009 and secured funding for the class from the Nokia Research Center in Africa. User-centered design starts with users, and there was important research to be done on the ground first—identifying health-related sites (clinics, hospitals) and meeting the people who run and attend them (community leaders, government representatives, health workers, patients). But there was no time for Stanford students to go to Nairobi before or during the class. Instead, they forged a partnership with Peter Waiganjo Wagacha, Daniel Orwa Ochieng, Judith Wawira Kamau, and Samuel Ruhiu from the University of Nairobi’s School of Computing and Informatics who, with a team of 27 of their students and advice from Jussi Impiö of Nokia Research Center, dedicated time to the research effort—the results of which were presented to Cohen and Winograd just before the start of the class.

At Stanford, 80 students applied for 20 places in the new class. Cohen and Winograd chose participants based on their experience and field of study. “We wanted the class to be as multidisciplinary as possible so that expertise could be shared,” says Cohen. The Nairobi and Stanford groups were separated by almost 10,000 miles but very much connected through e-mail, Facebook, phones, and teleconferencing—successfully tag-teaming throughout the quarter.

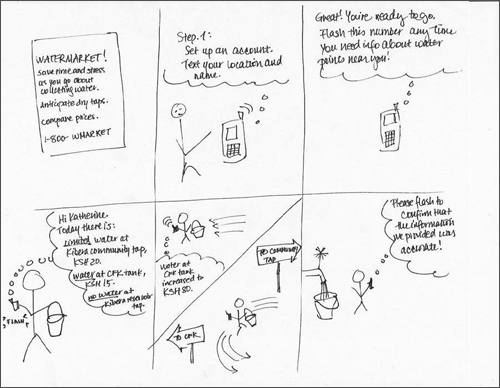

Six Stanford teams came up with proposals to realize solutions for issues raised by the Nairobi students—including use of mobile phones to locate malaria drugs and check them for counterfeiting, to help community health workers collect patient information and control patient workflow, and to locate and price quality water supplies. While all projects started from the premise that mobile phone technology would be used, some moved to other technologies and media once in development. “One of the foundations of user-centered design, as we teach it, is that technologies should not be imposed but should be derived from in-depth understanding of the needs,” says Winograd.

The first step for students in developing solutions was to appreciate the scope of the problems to be addressed. For a team exploring ways to use mobile phone technology to encourage pregnant women to save money for prenatal care, the research was especially compelling. Pregnancy in Kenya is a life-threatening condition where almost two women or girls die every hour from pregnancy-related complications. “Women are pregnant frequently in Kenya, where the average is five pregnancies in a lifetime. So it’s a huge health threat,” says David Wade Rizk ’10 (MPP ’12). “Helping to solve just this one challenge—saving for prenatal health care—has huge potential for saving lives.”

As projects developed, experts from Silicon Valley’s tech companies were invited to act as outside coaches to the teams—offering up their advice on project content and design process. “We were all busy, most of us taking a full course load, none of us with startup business development expertise. So having experts come in and walk us through some of the potential pitfalls that others have found when planning projects like ours was very useful,” says Joseph Giovannetti, JD/MS ’11.

At the end of 10 very intense weeks, the class teams finished their project proposals and three were chosen to continue into a summer exchange session with a trip to Africa. In August, six Stanford students, along with Cohen, traveled to Nairobi to explore possibilities for developing their projects further—particularly conducting research and identifying partners to help with field testing.

The University of Nairobi students and faculty were, Cohen says, wonderful hosts who helped the students navigate the city, as well as political and cultural differences. Once on the ground, two members of the “pill check” malaria drug team, Giovannetti and Yaa Oforiwa Opare (MA ’10), discovered the political nuances of their endeavor. “Some people working in government hospitals and clinics wouldn’t say anything disparaging about the government’s efforts—there’s plenty of malaria medicine to go around, all pharmacies are licensed, counterfeit drugs are not widely sold. That was their ‘line,’ ” says Giovannetti. “But we found the reality very different in poor communities we visited. A woman running a small pharmacy in Kibera admitted to selling three tiers of drugs: brand name, generic, and counterfeit. She may not have understood the repercussions of the counterfeit drugs, that they might be delivering a death sentence to someone. She seemed to view them as simply the cheapest option. And there’s a market for the cheapest option in a community that poor.”

In September, it was Stanford’s turn to play host when the Nairobi faculty and students visited campus for a “design thinking” workshop and meetings with various Silicon Valley companies.

There were some hiccups along the way—the partnership with the University of Nairobi was almost derailed at one point when political unrest at the university closed the campus—but the project was a great success not only academically but in human terms as well.

“I came to Stanford because I was interested in technology, law, and policy. This class showed me how technology can be transformative, not only for Silicon Valley but the world over,” says Rizk. As for how the class relates to his plans to practice IP law, he adds, “This class required very close teamwork and collaboration across national boundaries. That experience alone is already helpful.”

“The class was all about real-world experience—coming up with tangible projects that have the potential to become real tools to provide a life-saving service,” adds Giovannetti. He is clear that the experience will benefit his career practicing law. “Investigating an issue that I knew nothing about, quickly getting up to speed about various aspects of the problem, meeting and talking with people affected by it—that’s what lawyers do.”

While some of the projects begun last spring are still in development, Cohen and Winograd are already planning for the next class. “We think it is important to marry the excitement and promise of mobile development with the insights of user-centered design,” says Cohen. “We see this first class as the beginning of a fruitful collaboration across disciplines and national boundaries, a collaboration that shows some real promise of innovative solutions that address real needs.” SL

3 Responses to “Designing Liberation Technologies”

Comments are closed.

Roger

Hi,

For me when i read this article. My initial reaction was funny because a mobile phone(or smart phone) specially coming from australia is used to browse the internet, or take pictures or videos. It is very interesting to use your mobile phone in this way. I’m not saying its bad. Thumbs up to the professors and students for their practical approach in applying technology such as mobile phones to make life easier for people in the developing world specially in kenya and Africa. Thanks.

michael

It’s about time Africa gets some help to move into the future with us. Thank you for the article.

Denis Corbeston

Every article about helping Africa move forward makes me so happy. Its about time people who care all over the world

will make and effort to help the Africans who suffer from sicknesses, dictators and poverty. Do you even grasp what a life expectancy of 57 year means? Thanks for an inspiring article.