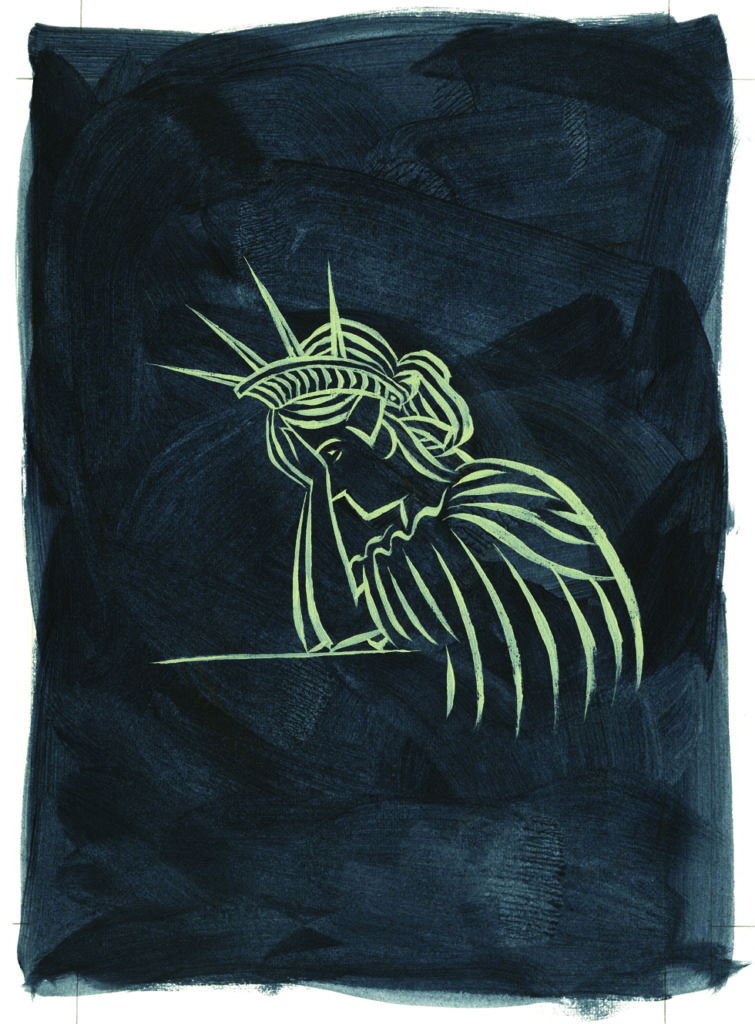

Post 9/11 Civil Liberties: A Conversation with Anthony D. Romero, and Deborah L. Rhode

Anthony D. Romero, JD ’90

Former Yankee’s manager Yogi Berra once said, “You don’t have to swing hard to hit a home run. If you got the timing, it’ll go.”

Timing matters, but so does the realization that it is your moment.

Anthony Romero didn’t have time to absorb the importance of his time and place when he was appointed executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union in 2001 and presented with the rare opportunity to have an impact—and to help shape the civil liberties debate in post-9/11 America.

Romero was barely 10 years out of law school when he was tapped to become the ACLU’s executive director. He had been at the Ford Foundation, where his work as director of human rights and international cooperation was getting attention. He was just 35 years old when in 2001 the ACLU’s national board voted unanimously to appoint him, in large part because of his youthful energy, his vision—and his personal experience of issues at the forefront of the organization’s mission.

Romero had grown up in a tough neighborhood in the Bronx, and eventually moved to the suburbs and graduated from Princeton University and Stanford Law School.

“I am one of the few for whom the system worked. The various safety nets and remedying vehicles all worked for me—everything from public housing to public schools to federal loans to affirmative action. I could be a poster boy for how American government works when it really wants to level the playing field for someone who wasn’t born with advantage,” he told Stanford Lawyer in the interview that follows. Romero is an openly gay, first-generation American of Puerto Rican heritage who was raised on the margins of society, but his belief in a just and fair system and his confidence that he could make a difference drove him—particularly after law school. “I figured out in law school that there was something I could do to make the world a better place. It sounds trite, but it was really a time of hope for me.”

And the ACLU was looking for someone like Romero, a fighter with a fresh vision. One of the oldest nonprofits in the country, it was founded in the post-WWI years, when fears of a Communist revolution brought a severe crackdown on dissent. The nascent ACLU took a stand—defending an unpopular position—that the rights guaranteed to Americans in the Constitution were constants, not conditional on war or peace.

Romero was the man of the moment when, in early September 2001, he took his seat at the helm of the ACLU. He was ready to dive into some of the most pressing issues of the time—marriage equality, immigration, privacy rights, affirmative action. He wanted to build the ACLU membership nationwide, but also diversify it. And he wanted to mobilize the base, so that, as he told The New York Times in 2001, “they would stand for the organization, rather than just having it stand for them.”

Romero had been on the job at the ACLU for just one week when terrorists flew planes into New York City’s World Trade Center Twin Towers and the Pentagon in a devastating series of attacks that came perilously close to the White House. And the ACLU’s founding mission was ignited anew with war—and new threats on civil liberties just around the corner.

Now 14 years into the job, Romero is a seasoned, enthusiastic champion of civil liberties. And he is upbeat about some important progress that has been made, particularly regarding marriage equality and immigration reform. But he’s also hunkering down for big campaigns on a number of fronts including mass incarceration and racial inequality in the prison system. And as Congress begins to consider re-authorization of the Patriot Act, he is lobbying hard to safeguard the privacy issues triggered by government surveillance, including those exposed by his client, Edward Snowden, two years ago. But he is at home leading this iconic organization. He has become an inspirational leader, raising more money for the ACLU than any other executive director in the organization’s history. He has also galvanized its more than 500,000 members (up from 300,000 in 2001) and strengthened its affiliates in 50 states. Today, questions about civil liberties are out in the light of day—front and center of the national debate.

Romero has shown he has great timing, and the self-awareness to know his value in the fight. He has become the face of civil liberties in America—the spokesman for the many issues the ACLU juggles daily. He is a man in his element, doing what he was meant to do at this time.

Deborah L. Rhode

Ernest W. McFarland Professor of Law

In her latest book, The Trouble with Lawyers, Deborah Rhode recalls how when she was a law student at Yale in the mid-1970s, she came face-to-face with both the desperate deficit of legal services for the poor in this country—and the intransigence of the legal profession. She was an intern with a legal aid office, where demand far outstripped the capacity to supply legal representation. So, Rhode and her colleagues created a simple “how to” kit—a precursor to the many tools now available online for self-representation. But the effort was quickly threatened with legal action by local bar association officials who charged them with the unauthorized practice of law.

Since that time, Rhode has dedicated her career to exploring ways to improve access to justice for the millions of people in the U.S. who can’t afford it—and to reforming the legal profession, which she believes is too rigid and self-protecting. She has also shown a spotlight on the challenges of practicing law in the United States, where an emphasis on billable hours and firm profits has compromised work/life balance and the provision of legal services through pro bono work.

“The current plight of indigent criminal and civil litigants is an embarrassment to any civilized nation, let alone one that considers itself a world leader on the rule of law,” she says.

While Rhode’s scholarship in this area has resulted in important papers and books, such as Access to Justice (2004), she has not been quietly tucked away in academia. She has agitated for change from within the American Bar Association as a member of the Committee on Professional Responsibility Section on Litigation (1987-1988) and the Commission on Women in the Profession (2000-2002). In 2008, she founded the Stanford Center on the Legal Profession and launched the Roadmap to Justice Project to bring greater visibility and expertise to the issues surrounding access to justice.

But her work does not stop there. Rhode is also one of the country’s leading scholars in the fields of legal ethics and gender, law, and public policy. An author of more than 20 books, including The Trouble with Lawyers, The Beauty Bias, Women and Leadership, and Moral Leadership, she is the nation’s most frequently cited scholar in legal ethics.

Rhode is a founding president of the International Association of Legal Ethics, a former president of the Association of American Law Schools, the founder and former director of Stanford’s Center on Ethics, the founding director of the Stanford Program on Social Entrepreneurship, and the former director of the Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford. She also served as senior counsel to the minority members of the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary on presidential impeachment issues during the Clinton administration. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and vice chair of the board of Legal Momentum (formerly the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund).

Rhode is also an advisor for Stanford Law students looking to pursue public interest careers. In 2003, Stanford Law School established the Deborah L. Rhode Public Interest Award, which is given annually to a graduating student who has demonstrated outstanding non-scholarly public service during law school.

In the following pages, Rhode and Romero discuss the work of the ACLU and civil liberty challenges facing Americans today. – By Sharon Driscoll

Rhode: The ACLU covers a broad range of issues from criminal law reform to free speech to immigration rights to national security—with lots of subsets for each. So, how do you prioritize?

Romero: You can’t be the ACLU, defending the rights of everyone everywhere, and say, “but we don’t do Native Americans and we don’t do pregnant workers and don’t bother us with your disability issue.” We have to keep a watching brief on all these issues. At the same time, when you look at our limited resources, there are places where we have a more unique strategic advantage than our sister groups in the field. You have to be consciously looking at the landscape and asking, “what can we do that’s going to add, what can we contribute, and what can we help put in place that other organizations cannot?”

Rhode: What’s the most difficult decision you’ve had to make as the executive director?

Romero: I think the most challenging was finding the right footing in the aftermath of 9/11.

Rhode: Am I right that 9/11 happened just a week after you were appointed executive director?

Romero: Right, yes. That was a moment where we could’ve gotten it all wrong. And I like to think we got it largely right. We could have, for example, pulled our punches about policies that we knew were going to come back to haunt us. We were opposing the Patriot Act a week after 9/11 and we were largely the lone voice. It’s hard to remember that, because the Patriot Act is so demonized—even by conservatives—and lacks credibility. But in the early days, we were very much the lone wolf. So we could’ve easily decided to tamp down our concerns for the sake of trying to go along to get along. But largely we didn’t do that. Historically, the ACLU has usually been in the right place, but not always. There were moments when we have gone along to get along and we’ve regretted that. One of my predecessors was too close for comfort to J. Edgar Hoover and we purged Communists from our board, including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and we shared minutes of our board meetings with FBI agents—it was seen as a necessary accommodation to Hoover’s aggression. I’d like to think that we learned a lesson from that sad chapter.

Rhode: So you had to calibrate the response, taking into account this national tragedy—

Romero: Yes. I think we could have been too shrill and too extreme to be taken seriously. I remember early on getting some blowback from my constituents that I was being a little too patriotic. The annual report in 2002 had the American flag on the cover and some thought it was too nationalistic. So there was some ambivalence about wrapping ourselves in the flag, but I was saying, “No, no. We have to wrap ourselves in the flag—we’re not going to relinquish the flag to anyone else.”

In my first week in this job, after 9/11, I put out an email to all of the staff all over the country asking that they refrain from talking about civil liberties violations. I said the focus needed to be on the 3,000 Americans who were killed, so I didn’t want our people out there crying about the civil liberties onslaught that we expected to come. I thought it important to meet our client, the country, where it was. So I said keep your powder dry and stay quiet. We’ll mourn the loss of life and as soon as they start changing laws, or policies, or programs that have an adverse effect on civil liberties, then we’ll go full guns. Here, I think we mostly got it right. The Great Recession was another big challenge, with lots of difficult decisions.

Rhode: Yes—tell us about navigating the ACLU through the Great Recession.

Romero: The market meltdown in 2007, 2008, 2009 was a nightmare. I’m a CEO at the end of the day, and so the mission and the values will get you only so far if you don’t have the money to actually turn them into programs. Some of our donors were going bankrupt, contributions were down, and income streams were not what they used to be. So we had to do some very difficult rounds of reductions in staff and cutting of expenses. I like to build the organization—I don’t like to take it apart. But those are necessary decisions when we have to be here for today, to have this thing powered, and still be here 100 years from now. And we will be. No one can imagine Harvard, or Stanford, or Princeton shuttering its doors, right? As long as we have an America, we’re going to have a Stanford. Well, it’s the same with the ACLU. We’ve been here for 95 years. This is not an organization where we’re ever going to be able to announce, “Mission accomplished! We’re done.” So we have to have the commitment to do the work today, but we must also have the long view—to keep the staying power and the vibrancy to endure for the next 100 years.

Rhode: You’ve said you’re proud of the ACLU’s decision to represent Edward Snowden. Do you think that whistleblowers who break the law should ever be punished?

Romero: I think we need to see whistleblowers as an essential part of a system of checks and balances. That’s not to say that everyone should get a blank check and be able to break the law whenever he or she feels like it, but we should be able to contextualize the reasons people step forward and release information that would otherwise remain secret and understand the context of it. So you have to look at these case by case. And I think you want to do it on the inverse of how we’re currently approaching it—that we have to look at what public good has been accomplished when a whistleblower steps forward. In any institution it sometimes takes the courage of whistleblowers to uncover wrong: whether they’re whistleblowers working in a factory plant and discover unsafe working conditions, or whistleblowers who step forward and talk about a hostile work environment and sexual harassment, or whistleblowers who uncover wrongdoing in the government.

Rhode: You called Snowden a patriot. Why?

Romero: You know, Ed Snowden stepped forward after watching many years of litigation and advocacy play out, to no effect. It wasn’t that we discovered the NSA or the surveillance issues once we got the first tranche of Snowden’s documents. We knew that these issues were a problem for our democracy. We had some indication, we had some evidence, and we had a great deal of doubt. It was only after he stepped forward, however, that we could substantively engage the legal issues. For instance, before Snowden, we brought two different lawsuits, one went all the way up to the Supreme Court challenging the surveillance programs, but we got kicked out because we didn’t have standing. So it’s a catch-22. How do you have standing in a court to challenge secret surveillance if you don’t know if you’re the subject of the secret surveillance? The very first document that Snowden revealed—the very first one—fixed my standing problem. It was not by happenstance. Now, I’m actually asserting some of the same arguments on the surveillance filing, the Fourth Amendment and Fifth Amendment, but I can get it over the procedural hurdles.

Rhode: So the government knew you had standing, but it took Snowden for it to be acknowledged?

Romero: You know, the government knew full well that we and our clients had standing to challenge the lawsuit—we just couldn’t prove it. And so it was only with the revelation of an Ed Snowden that we could prove we had standing. Whereas, the government knew all the time: “Well, these guys do have standing. They just can’t prove it, so we’re just gonna knock them out of court.”

We have to rethink the system. When all the cards are in the government’s hands, there’s got to be some kind of mechanism that allows civil society to come forward with bona fide, well-thought-out cases to proceed. I believe that when prosecutors have exculpatory evidence against a defendant, they have an affirmative obligation to turn over the exculpatory evidence. They don’t get to keep it secret and go ahead and try and convict the person. And something of that same kind of doctrine has to be evolved in a national security context.

Rhode: You said in a Boston Globe article that the most divisive case that the ACLU has worked on under your leadership is assisting the legal defense of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay.

Romero: Yes.

Rhode: That case seems very consistent with the ACLU’s history of defending unpopular defendants. What made this litigation so controversial?

Romero: You’re talking about the most infamous criminal defendants in modern American history, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. And when you say we’re going to spend a million dollars a year to bolster the defense team, defending the most notorious criminal defendant in the country, that inspires a lot of ire. I get these questions from liberals: “Why are you spending millions of dollars to defend the most high-value detainees? There are only five of them. You should spend that fighting for the detainees at Rikers or L.A. County Men’s Jail, instead.” And what I say is that the reason I think it’s incredibly important that we focus on Gitmo is that these are the most notorious crimes and we have totally jerry-rigged the system to ensure conviction. We’re not using our tried-and-true justice system, or the military system, or the civilian court, or the Article Three-court system. We’ve not resourced the defense functions properly; they’re the most hated of criminal defendants, and the policies and decisions that led to the torture, arrests, detention, and adjudication of these defendants have been set by the highest levels of our government. Torture happens at Rikers, but it’s not with the White House Office of Legal Counsel as its architects. However, the architects of the torture of the most high-value detainees happened in the West Wing—in the highest branch of the government. That, for me, kind of leapfrogs it into an injustice of enormous gravity, given the protagonists who were involved.

Rhode: Do you think Guantanamo can be closed? How do we move on from this legacy of what you’ve called a “human-rights-free” zone?

Romero: Guantanamo can certainly be closed. President Bush didn’t seek congressional approval in opening Guantanamo. And President Obama has the executive power to close it, should he wish to exercise it and fight a separation of powers lawsuit. The ability to decide whom to prosecute, when, and for what crime is exclusively reserved for the executive branch. That means Obama chooses not to run the gauntlet, not to pick the separation of powers argument, but one exists. We briefed it, we’ve presented it to the administration, and the administration just chose not to upset the apple cart. The closure of Guantanamo—the power to do it exists, but the political will appears lacking. RFK [Robert F. Kennedy] did not ask the permission of members of Congress or the Chicago City Council or the Chicago mayor when he went after Hoffa. It’s not how the justice system works. The executive branch and the Department of Justice exclusively have that prerogative.

And here, the president has put both hands behind his back, allows Congress to tie his hands, and then decries the fact that his hands have been tied. He’s been equally as complicit in allowing his hands to be tied. He chooses to allow them to be tied. It’s ironic. He has invoked the prosecutorial discretion to say, “I’m not going to deport these four million immigrants who can stay in this country; I’m gonna give them work visas.” He has totally used the executive prosecutorial discretion, the executive branch of powers to grant immigrants greater rights. He could use that same prosecutorial discretion of executive rights to close Gitmo and get the defendants in federal court. One gets him votes; the other gets him no votes—in fact, it might hurt him politically, which is why he hasn’t moved on Gitmo.

Rhode: Can you talk about another controversial case—your amicus brief in the Citizens United litigation, supporting unrestricted campaign expenditures by corporations as a form of constitutionally protected political speech. Did you worry about the consequences of allowing wealthy corporations such power in the political process?

Romero: Sure. So our brief in Citizens United and the opinion in Citizens United really are two different things, with the decision opening the floodgates for corporations to contribute directly into the coffers of the political candidates. If you go back and look at our brief, we ultimately did argue that the film on Hillary Clinton [Hillary: The Movie, a film critical of Clinton produced by Citizens United Productions and released in 2008] should not be banned by the campaign finance restrictions that were otherwise going to be invoked. So we made a more narrow argument—that the film was the prime example of political speech, that it was political speech when it matters most—around an election—and that it was important that the political speech be heard.

And, I think it’s important to say that this is an issue that has roiled my organization for the 15 years I’ve been here and at least the preceding 15. There’s no other issue that has been more debated by my board than this one. And I think everyone on our side believes that money can have a corrupting influence. And that there’s something fundamentally wrong with the role that money plays in our political system. And that, often, it’s the concern about how to remedy it. And then, I should say that after the Citizens United Supreme Court case, my board decided to revise its position on campaign finance and now accepts reasonable limits on both campaign contributions and expenditures.

Rhode: What are your thoughts on a fix for Citizens United?

Romero: We’re trying to find a new way to deal with the corrupting influence of money in the political sphere and, lamentably, there is no easy fix for the Citizens United problem. The only way to fix Citizens United would be with another Supreme Court case, which is not going to make much difference with the same composition of the Supreme Court, or through a constitutional amendment process, which we don’t believe is the right way to approach it at this moment. If we try to amend the First Amendment right now, in this political climate, with this Congress, we’ll end up with a weaker round of First Amendment protections.

I think for us, in the end, we need to think creatively about what solutions will help address the money and politics problem: I think greater disclosure and I certainly think greater strictures and the taxing of big players in the political sphere. We can look to possibly the nonprofit, IRS statutes as an example—the excise taxes that are placed on foundations, the limits on political speech in C3s, the prohibitions on electoral activity on C4s.

What’s unusual now is that all of these restrictions exist in the nonprofit world, but they don’t exist in the super-PAC 527s or the for-profit world. And I think we need to kind of use some of the same restrictions that are in place in the nonprofit sphere, as a way to harness it in the for-profit sphere. All of this is new thinking that we’re now just engaged in.

Rhode: At the helm of the ACLU, you have a lot of important decisions to make—where to put resources, how to cut them in a recession, how to calibrate responses after a national tragedy and during wartime, etc. What have been the biggest challenges during your tenure at the ACLU?

Romero: I think cynicism and fear are our two biggest challenges. Fear that we won’t get it right and cynicism that there’s nothing we can do to change it. And the only real antidote to fear and cynicism is hope and optimism. We can’t build a more perfect union based on fear and cynicism.

I think the greatest challenge is right now in the Obama years. It’s ironic, but we had no problem convincing people of the importance of civil liberties and civil rights in the Bush years. That was a moment when people got it and people reacted. Somehow, a quiet acquiescence has enveloped the folks who were previously enraged, motivated, and engaged; now they are a bit more complacent—maybe a little more cynical.

Rhode: It is ironic. And you’ve said that, if anything, the situation has worsened under the Obama administration—that since you’ve been in this position, you’ve seen the rise of anti-democratic politics and policies with the rule of law in peril. Can you talk about that a bit more?

Romero: You know, I think, on the positive side of Obama’s legacy, there’s been enormous progress in LGBT rights, there’s been an effort to reinvigorate civil rights enforcement, and the president has certainly been better than his predecessor on a right to choice and reproductive rights. My big concern with Obama’s legacy is in the context of national security, where this is a president who continues to use the Guantanamo military commissions to prosecute individuals for the 9/11 attacks—a system that is not working, will never work, and should never be used. Right? And yet he persists in using it.

The president inherited and then grew, expansively, the use of drones: It’s a breath-taking use of executive power when the president of the United States uses the full fury of the Defense Department to go after an American citizen, without any mediating institution, for death outside the specter of the battlefield. So when he went after Anwar al-Awlaki and we killed Awlaki and then called his 16-year-old son collateral consequences, that was just too far to discount in this. Yemen was not an active battlefield. You don’t get to send the Department of Defense, hunting the head of a U.S. citizen, without some kind of legitimate adjudicative process.

This is a president that—not withstanding his rhetoric around transparency and accountability—has invoked the state secrets privilege and has targeted more whistleblowers for prosecution than any prior president.

Rhode: The tale of two presidents?

Romero: Yes, indeed. I think you have this tale of two legacies. On the one hand, you have a president who has championed rights and opportunities that affect millions of Americans and real constituents. On the other hand, he’s been the defender of policies that he inherited and amplified, that have enormous implications for the rule of law, generally. The only way I can square these differences is that there are votes to be gained by defending the rights of immigrants, gays, and women for the Democratic Party. There are no votes to be gained, in domestic politics, by showing concern about the rights of high-value detainees or suspected terrorists overseas. I hate to break it down into this kind of realpolitik but it is vote counting.

So, one would have thought that a constitutional law professor would have had a greater concern. Even if there’s no domestic constituency attached to the likes of Guantanamo or drones or NSA surveillance—one would have thought that those things would’ve been a lot more troublesome to Obama—however, it appears we have more of a politician than a constitutional law professor in the Oval Office.

Rhode: What makes the ACLU so unique, such a mainstay of American life?

Romero: There are three things that distinguish us from other groups, where we use these three factors and say, okay, what can we do that’s different.

First, we have an office in every single state. So we have big headquarters in New York, we have a large lobbying operation in Washington, but, most importantly, we have boots on the ground in every single state—people on payroll, defending civil liberties and civil rights in this context. And we have about 1,000 staff on payroll and 660 of them are in the state offices. That’s what distinguishes us from any other group. And that is something I have zealously built. The affiliates are much bigger and stronger now than they ever were before I got here.

Second, I’d say what’s different for us is how we use our membership base. Because while we have very many generous benefactors, there are half a million people who, in the course of the year, write an average check of $60 to the ACLU. So they’re actually bodies, constituents. We’re not a stalking horse for any particular donor from any benefactor or foundation. This is really an organization for the people, by the people, and there happen to be individual ACLU members everywhere. So, how do we use our grassroots membership base as protagonists with us, rather than just checkbook benefactors?

Third, we employ an innovative advocacy approach to the issues. We’re probably the world’s largest public interest law firm, but we’re not a law firm. We’re a domestic human rights organization, so we litigate, we lobby, and we move public opinion and educate the public. There are a lot of other groups that are really great legal groups, there are some groups that are really great lobbying groups, there are some groups that are very good public education groups, but we have the distinction of having those three tools to move the needle forward.

Rhode: You were the recipient of the first-ever Stanford Public Interest Lawyer of the Year Award in 2004. There are many students and graduates who would like to follow in your footsteps. Can you say a bit about how you got to the ACLU, one of the most important civil liberties positions in the country?

Romero: Throughout my career, I’ve followed my passions and I always tell young people if they do that which they’re passionate about, they’re going to do it exceedingly well and they’ll do a lot of it. And that would be the key to their success.

I’ve been very fortunate. I’ve been given opportunities that were literally unthinkable to me, as a kid growing up in the Bronx. I never imagined I would go college, never mind Stanford Law School.

One of the things that I really understood while I was at Stanford was that I was one of the fortunate few for whom the system worked. The various safety nets and remedying vehicles all worked for me. Everything from public housing to public schools, to federal loans, to a scholarship, to affirmative-action programs. I could be a poster boy for how American government works when it really wants to level the playing field for someone who wasn’t born with the advantages of others. As I learned in law school, these systems weren’t all just by happenstance, but a part of good social engineering and good advocacy, both in the courts and in legislatures, to provide the very type of programs that made my career possible. I didn’t know until I got to law school that affirmative action was a vigorously fought-for win. I didn’t realize there were generations of people before me who had fought for the ability of that program to exist, so that I, and others, would be given a shot at making a difference.

Rhode: We need more people like you to be out front about affirmative action.

Romero: I never would’ve got into Princeton if there hadn’t been conscious affirmative-action programs to get underprivileged and minorities students. I probably would not have been admitted to Stanford had there not been a commitment to inclusion and diversity. My LSAT scores were not comparable to those of other students in my law school class. I can say that and not be at all embarrassed because I am every bit as good as any one of my contemporaries graduating from this school.

Rhode: It turned out all right in the end—

Romero: It did turn out all right in the end. They took a chance and I like to think I made them proud. And I got so much too. I reflected upon what Stanford’s given me, as I was riding the subway to come back to the office to talk to you. Stanford taught me about the potential to contribute to social change. I figured it out in law school—that there was something I could do to make the world a better place. It sounds so trite and inane, but it was really the first time for me. In college, I learned how to deconstruct everything and look at whatever was wrong, or broken, or unfair—that’s what political science classes do, what anthropology classes do, and what social science classes do. But law school taught me how to make it better—as well as what role you could play and what responsibility you have. I definitely worked hard, I definitely had raw talent—but working hard and raw talent would have gotten me nowhere had it not been for the equity programs that I fully benefited from, the best of which was affirmative action. Affirmative action changed my life. I am a proud beneficiary of aggressive affirmative action.

Rhode: Do you have any career advice for law students?

Romero: I think Stanford Law School does an outstanding job preparing them intellectually for the leadership roles that they invariably will assume. But law school often has a sort of a one-size-fits-all approach to a legal path, and I think there are many other detours for people to take to be in the right job. Experiential learning and the mapping of one’s non-intellectual skill set are equally important. Students need to ask themselves not only, “What type of law do I want to practice?” They need to dig deeper and also ask, “Am I someone who likes to work with people?” If so, you might want to think about a job where you have intake and you hear lots of input and you cull through it all and bring the jewels of the cases. If you’re a lawyer who likes to sit in the library and think theory and strategy, then you’re an appellate litigator. If you’re someone who really likes public presentation and gets a thrill out of being in front of other people, then let’s consider a trial role for you. So you have to tap into your specific skill.

Rhode: What about advice for those who want to take on leadership roles in the nonprofit sector? Can you say anything about how they should prepare?

Romero: I think leadership requires a lot of willingness to fail. We’re all so driven when we’re in these elite schools—but we don’t really know failure all that well. We’ve had setbacks, bad grades occasionally, but there are very few folks, right out of school, who know what real failure looks like. And real failure is where the learning comes. And not being afraid of that failure—getting outside your comfort zone, saying to yourself, “Let’s give this a whirl and see what this is like.”

Rhode: Yeah. I’m teaching a course next spring, Law, Leadership, and Social Change, and I will bring students your message: “This is a course about failure.”

Romero: Right. And also: “What did you learn from failure?” That’s what I ask my senior managers each year: What worked, what failed, and why? And it’s very hard for them to admit failure. We teach for success, but we don’t really teach about failure and we don’t teach about fundamental challenges and resilience, tenacity, modesty, humility, the ability to say, “I screwed up.” The ability to show that you hear people and you’re growing from it.

I went through a very hard time early in my tenure. It wasn’t necessarily assured that I would remain director. There was a very public campaign to oust me from the ACLU; it was even called Save the ACLU. It was incredibly painful; it was incredibly enervating. But I learned a lot. I learned the importance of copping to my mistakes, I learned resilience, I learned grit, I learned of poise and grace. And there was nothing that had taught me that before. I had to learn it all as I went along.

I was very fortunate to have a couple of mentors, two women, now retired, who were the heads of their own organizations. They walked me through it. They put their arms around my shoulders and kept me moving one step in front of the other. Had it not been for these two women—sharing with me that leadership is not always about glamour and nice pieces in alumni magazines, but that leadership is also messy and dirty and debilitating politics—I might not have gotten through it. But getting through that proved incredibly important.

Rhode: Thank you so much, Anthony. It’s been wonderful talking with you again.

Romero: No, no. I really appreciate it. It’s a real honor to have you interviewing me, thank you. SL