The Empiricists

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s proposed court-packing plan of 1937 sparked decades of debate about judicial susceptibility to outside influences. After the Supreme Court struck down crucial parts of the New Deal, the president unveiled a plan to expand the size of the bench to as many as 15 justices to gain control of the Court. Yet soon after, Justice Owen J. Roberts, a center “swing” voter, aligned his vote with liberal colleagues in a pivotal case—the so-called “switch in time that saved nine.” While the story of the switch is often recounted, there is wide disagreement as to its validity and extent. Some scholars point to “external” factors—such as the court-packing plan and FDR’s landslide election of 1936—to explain Owen Roberts’ shift. Others argue that “internal” factors—such as jurisprudence, litigation strategies, and legislative drafting—demonstrate that the shift was long coming and not nearly as responsive to external factors as commonly conjectured.

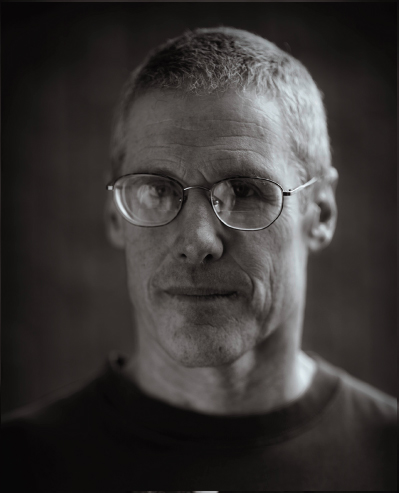

While volumes of ink have been spilled qualitatively studying this critical episode of constitutional history, Daniel E. Ho, associate professor of law and Robert E. Paradise Faculty Fellow for Excellence in Teaching and Research, and Kevin M. Quinn, professor of law at Berkeley Law, approached the subject quantitatively. Existing disagreements hinge in many ways on whether Roberts’ shift in votes was gradual and foreseeable or sudden and unexpected. Using modern statistical measurement methods, Ho and Quinn exhaustively studied the voting patterns of newly collected data—nonunanimous cases issued from the 1931 to 1940 terms. Results revealed that Justice Roberts switched abruptly and temporarily to the left in the 1936 term, giving credence—although by no means conclusive—to externalist accounts.

Ho and Quinn’s study is just one example of the trend in legal scholarship to employ various forms of empirical analysis to answer questions across many more areas of the law than ever before.

Today, legal empirical researchers are not only using statistical analysis to organize information, they are conducting experiments and generating their own data. Empirical legal studies has become an intellectual movement with far-reaching implications, the combination of legal analysis and data crunching influencing the development of law in myriad ways.

As legal empiricists continue to gather and share knowledge—launching the Society for Empirical Legal Studies, the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, and academic blogs devoted solely to the field—it’s clear that this burgeoning movement will be as important to the next generation of legal scholars as the law and economics movement was to the last. And Stanford Law School, an early pioneer, lies at its epicenter.

Testing the Theory

Stanford Law professors engaged in empirical research have PhDs in environmental science, political science, sociology, economics, and other disciplines that provide both an interdisciplinary framework for their scholarship as well as science-based tools for answering legal and public policy questions. Rather than rely on pure theorizing, empirical studies offer ways to test causal relationships and the efficacy of legal interventions across all specialties, from employment law to corporate law to civil rights law.

This emphasis on empiricism has long been brewing as legal theories, abstract ideology, and normative arguments have morphed into tangible questions that can be empirically framed.

“From the ’70s to the early 2000s, major breakthroughs were made across fields of law that were largely theoretical,” explains Larry Kramer, Richard E. Lang Professor of Law and Dean. “Now people want to test whether those things are true, whether the theories actually explain how things do or can work.”

“Scholars can spend only so much time debating legal theory,” adds Jeff Strnad, Charles A. Beardsley Professor of Law. “Real-world studies make sense because law is an applied discipline.”

When two theories of human behavior or institutional operation conflict, “you need to start counting,” notes Michael Klausner, Nancy and Charles Munger Professor of Business and professor of law, who conducted an empirical study of anti-takeover protection in IPOs.

The Information Explosion

Some legal scholars have engaged in empirical research for decades. Lawrence M. Friedman, Marion Rice Kirkwood Professor of Law, was (and still is) at the movement’s forefront, for example, with his groundbreaking empirical scholarship drawing upon data painstakingly culled from boxes and boxes of paper court records. From the 1964 publication of his “Patterns of Testation in the 19th Century: A Study of Essex County (New Jersey) Wills” to his 2009 examination of the impact of inheritance in Dead Hands: A Social History of Wills, Trusts, and Inheritance Law, Friedman’s work has been a model for legal empiricists. And his contribution to the field as a mentor is equally important: Friedman is an academic advisor to advanced degree students in the Stanford Program in International Legal Studies, through which graduate students engage in interdisciplinary research using empirically based methods adapted from the social sciences, economics, and other disciplines.

Still, there has been a generational shift, driven by technology and the ensuing information explosion, which has offered not only more data but also a multitude of new avenues through which to obtain and analyze it.

A hallmark of the empirical legal studies movement is the application of statistical methodology—including “Bayesian” data analysis—to questions of description, prediction, and causation. Clarifying the relationship between theory and evidence with a quantitative framework, the Bayes formula calculates probabilities based on new evidence. Applying such approaches to scientific, and now legal, questions has become far easier with advances in supercomputers that efficiently collect and scrub data.

While Stanford University has long been known for its supercomputing, the law school has, in its own right, been at the forefront of law-related data crunching, supporting empirical research for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers.

“More and more of the best people on the market are doing empirical work, and they need a state-of-the-art computational infrastructure to do so,” Kramer says. “The law school’s IT department supports a large group of faculty with serious training in empirical research, much more than other schools that are bigger.” In addition to employing 10 full-time research fellows and a team of IT experts specifically dedicated to working on empirical research, the law school is also building one of the best IT infrastructures in the country.

“We’ve shifted a significant portion of the IT budget to support faculty data analysis because the need in this area is so great,” says Jason Watson, Stanford Law’s chief technical officer. Watson explains that expanded IT services to enable and enhance faculty empirical research include identification, aggregation and storage of structured and unstructured data collections; establishment of version control servers for iterative and collaborative work products; expansion of online data storage capacity; and augmentation of the computational infrastructure to allow for increased data analysis capabilities.

Fully utilizing the law school’s computer resources, the Intellectual Property Litigation Clearinghouse, founded by Mark A. Lemley (BA ’88), William H. Neukom Professor of Law, is on track to become the largest legal empirical database in the United States. This free online tool provides real-time data—across roughly a billion data facets—on intellectual property litigation. A new private-venture outgrowth of that clearinghouse, Lex Machina, launched early this year. Similarly, Deborah R. Hensler, Judge John W. Ford Professor of Dispute Resolution and associate dean for graduate studies, directs Stanford Law School’s Global Class Actions Exchange, an online clearinghouse providing country reports, statutes, rules, and cases for scholars and practitioners who empirically research collective litigation practices. Hensler was the director of RAND Corporation’s Institute for Civil Justice and is an expert in international class actions with more than 40 years of experience in empirical analysis.

Informing Policy Decisions

“Many scholars are turning to empirical work because crucial questions of law and policy turn on what’s actually happening,” says Ho, whose PhD in political science included a focus on statistical methodology and who has empirically examined such questions as whether media consolidation stifles viewpoints and the historical origins of the standing doctrine.

“Public policy and legal problems are much more serious and difficult to tackle,” says Joan Petersilia, Adelbert H. Sweet Professor of Law and faculty co-director of the Stanford Criminal Justice Center. Empirical research is the basis of her work on recidivism and how prisoners return to communities. Before joining Stanford, she served as an advisor to Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, implementing prison and parole reform, and as the director of the Criminal Justice Program at the RAND Corporation. According to Petersilia, lawmakers are increasingly turning to academics when making decisions.

“Work from the books is now getting translated to the streets as scholars and policymakers are studying how laws get implemented and what the consequences are. There’s a real yearning for academia to become more relevant,” she adds.

Because they rely on widely acknowledged rules of inference—and are thereby perceived as politically neutral and arguably more persuasive—empirical legal studies have considerable potential to influence public policy. For example, Petersilia introduced California policymakers to the concept of earned discharge parole, designed to allow low-risk parolees to earn their way off parole early. Petersilia’s academic paper detailing her research on the subject was attached to Governor Schwarzenegger’s press release announcing a pilot project. “It was the first time in my experience that a press release pertaining to corrections had ever been accompanied by an academic article supporting the policy scientifically,” she says.

Data Access and Obstacles

Like any methodology, empirical research is not without challenges or flaws. Despite sophisticated statistical methods, the resulting inferences are only as good as the data on which researchers rely. And some questions simply cannot be studied because of privacy and legal issues limiting access to data.

Alison D. Morantz, associate professor of law and John A. Wilson Distinguished Faculty Scholar, uses applied econometrics to study occupational safety and health laws and the economics of workplace regulation. One of her current studies examines confidential data related to occupational injury claims in Texas, the only state in the nation where companies are allowed to opt out of the state-run workers’ compensation system. To gain access to the data that firms use to administer claims (which are usually held by third parties), she spent more than two years building relationships with executives at large, multistate companies that chose to opt out.

“Much of the data for empirical study—the tools of our trade—is sensitive, either because the company treats it as confidential or because it implicates individuals’ rights to privacy. For my study, there were obstacles to overcome before even starting, such as access to employee health records, which are protected by a fairly complicated thicket of legal and quasi-legal regulations. So the first step in this field is often building relationships and negotiating access to data—allaying legal concerns, answering general counsels’ questions about how the data will be used, etc. Fortunately, as lawyers ourselves, we are ideally positioned to negotiate agreements and address legal concerns,” says Morantz.

Funded by the National Science Foundation, Morantz’s study looks at how large firms’ decisions to provide their own occupational-injury benefit plans in lieu of statutory workers’ compensation affects the frequency of claims, the cost of claims, the amount of lost work time, the overall cost to firms, and other outcomes. Her findings could, among other things, indicate which revisions to state workers’ compensation laws are likely to produce the greatest cost savings and could ultimately help lawmakers in other states decide whether to make participation in their own workers’ compensation systems voluntary.

Although Morantz was successful in gaining access to important data for this study, that is not always the case. “Availability of data, or the lack thereof, determines what we as scholars can actually study,” she explains. “There are two approaches. One is to be a data scavenger. This is the car-keys-under-the-streetlight approach that says ‘Okay, the light is shining on the census, so what questions can I answer with that data?’ But there are a lot of important questions about which pertinent data are not readily available. To explore those questions, you have to spend time waging a campaign to figure out how to get your hands on the right data. And sometimes you lose. Sometimes you find the perfect dataset, but you can’t convince the people who have it to collaborate with you.”

Observational Data: The Nature of the World

While studies that rely on experimental data are increasing in popularity, empirical legal studies still rely primarily on observational (non-experimental) data—as is the case throughout much of the empirical social sciences.

“We’re not doing double-blind random assignments like they are in medicine because, in many cases, it would be unconstitutional,” Strnad explains. “If we’re studying the impact of abortion laws on crime, we can’t randomly assign women to have abortions.” Petersilia provides another example: “We can’t randomly assign children parents who are incarcerated.”

Even with solid experiments and data, legal questions—especially those involving causation—are not necessarily answerable. For example, does unemployment cause crime or does crime cause unemployment? “The fact that the two are associated positively does not tell you which causes which,” Strnad says. “Unpacking causality using only observational data is very tricky.”

Randomized field experiments are the scientific gold standard, but in law things are rarely done randomly. Importantly, though, “randomized doesn’t mean capricious,” Petersilia notes. “It means equal probability of treatment. And we can apply that standard to law. The challenges are not really so daunting.”

Purely descriptive empirical work is as valuable as experimental data, according to Mark G. Kelman, James C. Gaither Professor of Law and vice dean. “It’s important to study the actual nature of the world that is subject to legal regulation—even if we don’t know why.” For his part, when examining an education statute alone left a gap in understanding, Kelman conducted surveys and interviews to examine how, exactly, school districts handle kids with learning disabilities. But he has conducted experiments too. For example, to determine how jurors, consumers, and voters make decisions, he ran experiments to monitor how people engage in moral reasoning tasks.

Real-World Relevance

Empirical research is also making its way from scholarship into the classroom where students are learning how to critically interpret—and in some cases, conduct—empirical studies.

In Klausner’s seminar on corporate governance, for example, students analyze the question: What is good governance? “The only way to answer that,” he says, “is to read studies.”

Similarly, real-world evidence “illustrates for students why certain laws are good or bad,” adds Daniel P. Kessler ’93, professor of law, who has examined how tax policy affects medical spending. In empirical research, “there is so much opportunity out there, and much is waiting to be done.”

One task for empirically minded law professors, according to Ho, is to “help future lawyers develop skills to consume quantitative analysis with some degree of sophistication. In antitrust, lawyers may depose an expert witness who provides quantitative evidence about market effects. In an antidiscrimination case, lawyers may have to sort out dueling expert studies of wage differences between groups of employees.”

Courses on quantitative methods and how to conduct empirical research are useful not only for law students who plan to become scholars but also to law students who plan to be practicing lawyers. In area after area—corporate law, intellectual property law, health law, environmental law, and more—lawyers need to be able to read, understand, and utilize sophisticated empirical work, whether litigating, advising, or doing transactional work.

“In academics, you can choose not to do empirical work. But in the field, you can’t choose not to,” Strnad says. “A lot of issues in law involve probability. With DNA evidence, for example, there’s a probability that this sample came from the defendant.” Strnad’s remedial and graduate-level statistics courses are triple-listed in the law school and with the wider university’s programs in public policy and international policy.

Strnad wants future lawyers to have a conceptual knowledge of statistics so they can “interpret the output” of studies and maintain confidence when facing experts. That, he believes, is more important than the number crunching or “creating the output.”

Strong statistical skills translate into “a big edge in the job market,” he adds. “Alumni [at law firms] are unbelievably enthusiastic about students getting this training.”

For their part, students are “incredibly excited about something real world,” Petersilia says. “They can wrap their minds around it. It may not be on the bar exam, but students are really hungry to get away from the doctrinal stuff.”

Empirical Studies at SLS: A Sample

∙ Daniel P. Kessler ’93, professor of law, works in conjunction with colleagues in the economics department and at the medical and business schools identifying the effect of malpractice laws on defensive medicine practices. Applying traditional economic analysis, Kessler analyzed malpractice liability reforms using data on Medicare beneficiaries treated for serious heart disease in 1984, 1987, and 1990. He found that malpractice reforms that directly reduce provider liability pressure lead to reductions of 5 percent to 9 percent in medical expenditures without substantial effects on mortality or medical complications. He concluded that liability reforms can reduce defensive medical practices. In another study, Kessler found that support for health-care reform drops once people realize how much it will cost them.

∙ In a study of outside director liability, Michael Klausner, Nancy and Charles Munger Professor of Business and professor of law, found that, popular opinion notwithstanding, outside directors are rarely held personally liable in derivative suits, securities class actions, or Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) enforcement actions. He’s now working on a follow-up article examining whether securities class actions supplement SEC enforcement. Casting uncertainty on the stated justification for these suits, he preliminarily concludes, “To the extent we are interested in imposing liability on culpable officers, it’s doubtful.” Klausner also co-authored an article, titled “Standardization and Innovation in Corporate Contracting (or The Economics of Boilerplate),” on standardization in corporate contracting. He showed that, as an empirical example of the standardization process, certain bond covenants became standardized over time but that the standard that emerged was not the most sensible for the parties.

∙ David Freeman Engstrom ’02, assistant professor of law, is conducting a systematic empirical analysis of qui tam litigation since the modern False Claims Act came into being in 1986. Engstrom is currently building a dataset with thousands of cases that will allow him to answer a wide range of questions raised by policymakers and by the Supreme Court in its recent decisions. Among other things, Engstrom hopes to delineate the characteristics of the “whistleblowers” who bring fraud cases on behalf of the United States, chart the role and influence of the U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. attorneys in co-prosecuting qui tam cases, and, more broadly, address the virtues and vices of private enforcement of public law (the so-called “private attorney general”).

∙ Robert M. Daines, Pritzker Professor of Law and Business, analyzed the effect of commercial corporate governance ratings on future performance, risk, and undesirable outcomes such as accounting restatements and shareholder litigation. He determined that claims of predictive validity by corporate governance rating firms and proxy advisory firms were not supported by real-world evidence.

∙ Joseph A. Grundfest ’78, W. A. Franke Professor of Law and Business, founded and directs the Securities Class Action Clearinghouse (SCAC), a free, online database of all securities class actions filed in U.S. federal court since the passage of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) of 1995. SCAC is a leading source of detailed, historical analyses of securities fraud class action litigation and serves as a research tool for investors, policymakers, scholars, judges, lawyers, and the media. The clearinghouse maintains an index of filings of more than 3,000 issuers that have been named in federal class action securities fraud lawsuits. The full text of complaints, motions, dockets, judicial opinions, and other class action filings, together with summaries and analyses of those lawsuits, are digitized and linked into a website with its own full-text search engine, useful to anyone conducting empirical studies in this field. Research compiled by SCAC is frequently referenced in both the mainstream media and scholarship.

Leslie A. Gordon is a San Francisco-based journalist whose work has appeared in California Lawyer, The San Francisco Chronicle, and San Francisco Attorney Magazine, among other publications.

1 Response to “The Empiricists”

Comments are closed.

Bruce Cahan

The New York Matrimonial courts are presided over by judges, and host litigants represented by attorneys, who are members of the Women’s Bar Association (WBA).

As the feminist movement enters its golden years, Stanford faculty should aim their quantitative lenses on the gender bias of wrenching children, marital and post-marital wealth away from fathers caught up in the New York matrimonial courts.

My preliminary analysis on the average number of motions and delays in hearing motions brought by attorneys who at members of the WBA vs nonmembers shows the systemic bias towards judicial indulgence of WBA members. Add to this sexism the fact that Democratic Party bosses anoint judicial nominees (Bd. of Elections v. Lopez), and New York’s matrimonial courtrooms are a cesspool of influence peddling and forensic supplicants whose tendencies for patrimonial abuse and alienation go unchecked and largely unseen (much of matrimonial court process is unpublished).

Despite two studies of the rights of women in the New York State courts authorized by the state’s Chief Judges, no study has been done to check whether the rights of women came at the undue expense of men, especially in the intimate backwaters of family law and matrimonial litigation.